6 June

2017

Obviously, the pace of traveling in a car—even with

scheduled walks along the way—is very different than walking the bulk of the

way across the countryside, and the biggest difference is the view beyond the

hedges. There is a limited view from the roads and though we are not

infrequently gasping with pleasure at vistas that open up before us through a

break in the hedge, some of what we drive through feels like being in either a

maze or a tunnel of trees.

We

reached Glastonbury on Friday, with much discussion on the topic of King Arthur

and whether he was a fictional or historical character (I am firmly in the

former camp). The “Welcome to Glastonbury” sign actually identifies the place

as the “Isle of Avalon,” and I was intrigued to discover if the crystal-gazing New

Age philosophy that dominated the place when I was there in 1997 is still in evidence.

It is.

Twenty Years Ago in Glastonbury: A store in the city centre, New Age pilgrims at the Chalice Well, and Glastonbury Tor from the Abbey

Twenty Years Ago: The

Age of Aquarius

Though the rain did not pour down as

hard as it had on the previous day the dawning of day three was wet enough to

dampen the spirits of the night before.

At breakfast I pondered the map again; there were no footpaths at all

that could reasonably constitute a route between Wells and Glastonbury. To argue in favor of walking, it was almost

completely flat, over moors with names like Queen’s Sedge, Splotts, and

Crannel, all connected by criss-crossing canals. The major argument against walking was that

it would be entirely along the A39 which I had grown to hate. I had asked yesterday at the Information

office if there were boats that travelled the canals and was treated with a

shake of the head and a look halfway between paternalistic and

patronizing. No busses ran on Sunday

morning. My feet seemed better, but my

calves were knotted tight and sore.

Before I called a cab, and then again

as I waited for the one I did call, I engaged in a serious bout of self

justification. It had been very easy to

declare from my dining room table at home that nothing would keep me from

walking every step of the way across England.

Wainwright had, after all, refused a ride during a howling gale on a

desolate mountainside. “I should have

had to be bound and gagged before I would have ridden in that car,” he

wrote. “I was pledged to do this trip on

my feet. ... If I had climbed into that car, my whole holiday would have been

irretrievably ruined.” But after only

two days walking I knew that I was no Wainwright.

Belloc never made a declaration about

walking in his book, and only in passing acknowledged “the baker’s cart which

had taken us along many miles of road so swiftly and so well: a cart of which I

have not spoken any more than I have of the good taverns we sat in, or of the

curious people we met.” Shirley du

Boulay, an English woman who followed Belloc’s pilgrim path from Winchester to

Canterbury and described the adventure in her book The Road to Canterbury

in 1994, did pledge to walk every step (somewhat stubbornly, she confessed),

but she and her companions were greatly assisted by a friend with a car who

picked them up at the end of each day’s walk and delivered them again the next

morning. And Sean Jennett, in his guide

to The Pilgrims’ Way: from Winchester to Canterbury recommends the bus

for several stretches of the path in no-nonsense terms. As to the Wife of Bath? “She rode a horse,” I reminded myself again

as I tossed my pack into the boot of the cab.

It was on to Glastonbury, where it had

been my intention from the first days of planning the pilgrimage to stay at the

George and Pilgrims Inn if I could get a room there. This was an ancient place that had been

rebuilt by Abbot John Selwood in 1475 just to accommodate pilgrims. Not knowing what vagaries might influence my

schedule, I had made no reservations in advance, and it seemed serendipity to

find that not only was there a room available, but it was the Henry VIII

room. They made no claims that Henry

VIII actually stayed in the room, though he is known to have made a pilgrimage

to Glastonbury, “but Jerry Hall stayed in that room,” the young woman at the

desk told me. The exterior was cut

stone, the interior half-timbered; the brochure and postcards featured my room

with a promise that one could “conjure up dreams of the past” there. Perfect.

For many centuries Glastonbury was the

most important pilgrimage site in England.

It took Canterbury and the events of the life and death of Thomas Becket

to dislodge it from its position. Today

it has regained its preeminence and in a way that was first brought to my

attention as I looked out the window of my room on the second story and front

of the house. Out the window I could see

the small square with its market cross and a great row of old buildings, one

with a sign identifying it as “Archangel Michael’s Soul Therapy Centre,

Providing Tools for Personal and Planetary Ascension.”

It was Sunday morning and not yet ten

o’clock when I arrived in Glastonbury, so I got out my reference materials and took

a stroll around town waiting for the Abbey to open. I would be the first in line. From several vantage points I could see

Glastonbury Tor, the hill which was hugged by the town on its western flank; on

its summit sits another site for pilgrims, St. Michael’s tower.

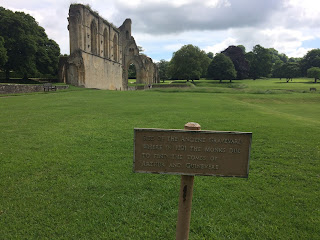

Glastonbury Abbey is a dramatic

ruin. There is a persistent story here

that Joseph of Arimathea, the rich man who provided the burial cave for Jesus,

came here with the Holy Grail some thirty-five years after the crucifixion

(and, consequently, some five years before the Romans). I even read in one local brochure that J. of

A., as a merchant trader, came here with the young Christ, his kinsman, during

those years when the gospelers are silent about the details of Jesus’

life.

There was certainly a church here in

the seventh century, and in 940 St. Dunstan became the Abbot and supervised the

building of a new Abbey, which was destroyed by fire in 1184. During the rebuilding, the monks announced that

they had discovered the graves of King Arthur and Queen Guinevere on their

grounds, and onto that great story were heaped others, including a visit by St.

Patrick. If one is willing to suspend

historical reason one can find at Glastonbury the justification for any number

of pilgrimages.

During the reign of Henry VIII, this

abbey, like all the monastic enclaves across Britain, was “dissolved” by his

command, the treasures shipped back to London, the lead roofs stripped, and, in

the case of Glastonbury, the influential Catholic clergy executed. As the walls deteriorated, local people

removed the stones to build houses and pave roads. But in its first incarnation as a pilgrimage

site, Glastonbury Abbey was a sacred sight indeed. William of Malmesbury, writing about it in

1125 said “The stone pavement, the sides of the altar, and the altar itself are

so loaded, above and below, with relics packed together that there is no path

through the church, cemetery or cemetery chapel which is free from the ashes of

the blessed.” Today the only bones one

sees are the jaw bones of a whale, forming an arch over a disused entry. There is a small museum attached to the gift

shop which has a few nice pilgrimage items, including some pilgrim badges and

small vials and reliquaries.

On that Sunday morning, the ruins of

Glastonbury Abbey were mutely tragic.

Only the kitchen is left standing, but the “Lady Chapel” with its “Crypt

Chapel” dedicated to Joseph of Arimathea still has its walls largely intact. On the outside wall is a stone with “Jesus

Maria” carved into it, a touchstone for pilgrims for a thousand years and it

was for me as I laid my hand upon it.

There is a chapel dedicated to St. Patrick, also claimed as a visitor to

Glastonbury, and a thorn tree said to be a descendent of a tree on nearby Weary

All Hill, where an exhausted Joseph of Arimathea drove his staff into the

ground and it took root. I took a leaf

from the tree as a relic (and later bought another, dipped in copper, at the

souvenir shop.)

I stood for several minutes pondering

the sad little spot where once the black marble tomb of Arthur and Guinevere

had once stood before the high altar.

The grassy plot is marked off and an embarrassed looking steel-framed

sign mounted on a beige-painted metal shaft informs the tourist that there were

once bones here “thought to be” those of the Camelot duo. In a moment of inspiration I chewed off a

fingernail and dropped it into the grass, a relic of myself.

For the pilgrim who seeks the past in

the landscape there is much to ponder here.

We know a lot about Arthur: we

know of his idealistic notions of government, of his accidental incest with his

sister which produced his dysfunctional son Mordred, of his menage a trois with Guinevere and

Lancelot, of the court he created with the Knights of the Round Table, and of

their quest for the Holy Grail (which, handily was right here in Glastonbury,

though they never found it). What we

don’t know is whether he actually lived.

If there was an Arthur, he was not the man we know from folklore and

literature.

It is clear from the sign and from the

literature available that the folks at Glastonbury Abbey are not trying to

prove the existence of a historical Arthur just because they happen to have his

grave on their premises. One of the

guide books says: “In this grave were laid bones thought to be those of King

Arthur and his Queen, Guinevere. Their

graves were discovered in the Abbey graveyard in 1191. King Arthur was probably a Chief who helped

to defend this part of the country against the pagan Saxons. The stories of the Round table came many

years after his death.” Not quite a

declaration of belief.

Few historians today doubt that the

discovery of the bones was a medieval hoax, a way of bringing attention to the

Abbey at a time when its fortunes were at their lowest following a devastating

fire. It was an age of relics and false

relics, and the knowledge that the Norman Plantagenet Kings were looking to

link themselves to a Saxon-fighting royal lineage in Britain made Arthur a

brilliant choice. Henry II had died just

two years earlier, Richard the Lionhearted was on the throne, and his nephew

and potential heir was Arthur, Duke of Brittany.

The thirty-five year reign of Henry II

solidified Norman rule in Britain and his marriage to Eleanor of Aquitaine

brought additional territory on the continent.

Henry had been raised on the tale of Arthur as penned in 1138 by

Geoffrey of Monmouth, a member of his father’s court. If Geoffrey were writing today, his book, the

Historia regum Britanniae or “History of the Kings of Britain,” would be

categorized by the Library of Congress as “historical fiction.” He incorporated into his book a number of

earlier historical sources, but where the story bogged down, where it lacked

romance, or where alteration could advance political motivations, Geoffrey

filled in, and Arthur was born. Thus we

find an Arthur who defeats all comers on the Continent, and whips the Saxons,

Irish, Scots, and Picts for good measure.

(He even has the bishops of the defeated Scots deliver up their relics.)

In her dandy small book, King Arthur

and the Knights of the Round Table, Anne Berthelot describes what happened

next.

“When Henry II was crowned King of England in 1154

he was quick to assess the political advantage to be gained from Geoffrey’s

work. ...The Plantagenet king therefore adopted a twofold strategy. He sought, on the one hand, to turn the

legend to his own advantage by presenting himself as King Arthur’s legitimate

heir, while simultaneously ... satisfying [the Bretons] with the existence of a

real Norman king, who had their interests at heart, rather than a figure of

myth. To this end (and with political

rather than literary notions in mind) Henry commissioned an Anglo-Norman cleric

at his court by the name of Wace to turn the Historia regum Britanniae

into a novel. What this meant was the

translation of the Latin text into the vernacular. ... Henry died in 1189. Shortly after his death the monks of

Glastonbury Abbey put the final touches to the revised version of the myth by

‘discovering’ the tomb of Arthur and Guinevere... it guaranteed the authenticity of the legend

and turned Arthur into a figure of undeniable historical reality, at the same

time enabling those who had played such an important role in his ‘invention’—the

Plantagenets—to bask in his reflected glory.”

Henry’s heirs certainly embraced their

relationship with Arthur. His son

Richard I is said to have presented Arthur’s sword Excalibur to King Tancred at

Catania while on a crusade. Another Arthur

would have succeeded Richard as king had he not been murdered by his uncle

John, who took the throne himself.

John’s grandson, Edward I, brought a book of Arthurian Romances with him

on a crusade, sponsored “Round Table” feasts, and was the recipient of Arthur’s

crown when it was “found” in 1284. And

when the Glastonbury bones were reinterred in a glorious black marble tomb in a

rebuilt Abbey, Edward himself carried Arthur’s coffin. His grandson Edward III is said to have been

inspired by the Knights of the Round Table in the creation of the Order of the

Garter.

I first became acquainted with Arthur

through the Disney cartoon “The Sword in the Stone,” and was inspired to read

Thomas Malory’s Morte D’Arthur after seeing the Monty Python movie

version of the search for the Holy Grail.

As a high school student I mistakenly thought Malory’s book, which first

appeared in 1460, was the original source of the story. A very important edition of Malory’s book

appeared in 1485, the year that the Tudors took power from the Plantagenets

with the defeat of Richard III by Henry VII.

Like his predecessors, the new King linked himself to Arthur,

christening his first son by that name in a ceremony at Winchester, a city identified

as Camelot by Malory. Even in the modern

age, Victoria and Albert found in Tennyson a writer who could do justice to the

Arthur saga, and they too gave the name to one of their numerous children. Arthurian murals decorated the walls of the

neo-medieval castle at Balmoral, and the pre-Raphaelite brotherhood was

illustrating every facet of the story in lush romantic paintings of red-haired

Guineveres.

There are two wonderful and important

things about Wace’s Roman de Brut, Malory’s Morte D’Arthur,

Tennyson’s “Idylls of the King,” and in fact all of the Arthur stories

following Geoffrey of Monmouth’s. Though

nominally set in the fifth or sixth century, the world described is the

medieval period in which the Plantagenets lived, with chivalrous armored

knights pledging chaste love to various ladies between quests, hunts, jousts,

and revels at court. And the stories are

so solidly grounded in the actual English landscape that I would walk where

Arthur was said to have walked on more than one occasion on my pilgrimage,

though never so strongly felt as here in Glastonbury.

The discovery of a grave made it seem

so historical, I guess. Bones are

evidence of a person, and there certainly have been a lot of people over the

last nine hundred years who have been willing to believe that that person was

Arthur. My friend Joannie, for instance,

when I told her I thought the grave was a hoax, held up her hand to silence me

and said, “Don’t tell me anymore. I

don’t want to know if it’s not true.”

Ralph Adams Cram, a noted architectural historian of the turn of the

century, wrote a book about The Ruined Abbeys of Great Britain in which

all his critical disbelief was suspended when Glastonbury was reached. “Whether we hold or discard the tradition

that St. Patrick first organized the scattered hermits of Avalon into a

semblance of order, or that Arthur and Guinevere lay here in a single grave,”

he wrote, “enough and more than enough remains, against which even modern

criticism is powerless, to make this the holiest land in Great Britain.” To Cram, the founding of the Abbey by Joseph

of Arimathea is “perfectly credible and also perfectly unprovable,” and the

fact that there was a grave proved that there was an Arthur.

“The

narrative of the finding of the bodies of Arthur and Guinevere during the

abbacy of Henry de Soliaco, in the year 1191, goes far to prove not only its

own truth, but the material fact of real existence as well: it is concise,

detailed, convincing, full of internal evidences of perfect veracity; if false,

it is a masterpiece of circumstantial evidence quite unimaginable in the

twelfth century.

Giraldus

Cambrensis, declaring himself an eye-witness, sets down the facts simply and in

the most matter-of-fact way. Between the

two mysterious pyramids beside the chapel of the Blessed Virgin, seven feet

below the surface, was found a large flat stone, in the under side of which was

set a rude leaden cross, which, on being removed, revealed on its inner and

unexposed surface the roughly fashioned inscription, ‘Hic jacet sepultus

inclitus Rex Arthurius in Insula Avalonia.’

Nine feet below this lay an huge coffin of hollowed oak, wherein were

found two cavities, the larger containing a man’s bones of enormous size, the

skull bearing ten sword wounds, the smaller the bones of a woman and a great tress

of golden hair, that on exposure to air crumbled into dust. ‘The Abbot and Convent receiving their

Remains with great joy, translated them to the great Church... where they rest

in magnificent Manner ‘til this Day.’

Here

facts fall and dissolve: the instant one stands in the shadow of these mighty

crags of riven masonry, all the inheritance of a thousand years comes back, and

we know that here also walked St. Joseph of Arimathea, St. Patrick, King Arthur

and his queen, and that beneath the vanished vaults once rested the Holy

Grail.”

There is plenty of evidence that

medieval confidence men were just as able to perpetuate scams as their modern

counterparts, and Cram places a ridiculous amount of faith in so-called

“eyewitness” testimony. There are many

medieval narratives that begin with the claim that everything therein was

witnessed by the author, and then go on to describe sheep growing on trees,

bands of Cyclops, and sea monsters; not to mention that at the time Arthur’s

tomb was discovered relics circulating around Europe included the staff of

Moses, samples of the manna from heaven, thorns from the crown of Jesus, and

enough pieces of the true cross to build a boardwalk back to the Holy Land.

In 1607 a man named William Camden

published a sketch he made of the lead cross with the inscription “HIC IACET SEPULTUS INCLITUS REX ARTURIUS IN INSULA

AVALONIA,” (“Here lies

buried the renowned King Arthur in the Isle of Avalon”), but the cross itself

disappeared sometime in the next hundred years.

Camden’s picture of this crucial piece of lost evidence has been the

subject of much speculation. Geoffrey

Ashe, a historian who has written some eight books on King Arthur is convinced

by the fact that the “ clumsy lettering does not suggest the style of the twelfth

century, and the Latin spelling Arturius is an archaic form which was used five

hundred years earlier.” Like Cram, Ashe

does not credit that good fakers of the twelfth century might also have thought

of that.

In his book The Discovery of King

Arthur, Ashe makes a very compelling argument for the existence of a real

Arthur in the person of a king known in early texts as Riothamus. Filled with knowledgeable detail about the

invasions of Romans, Saxons, and Normans into Britain, and wonderfully complete

in its discussion of all of the early sources of the Arthur legend, the book

builds, layer by layer, a very convincing argument that there was an

actual Arthur whom we would recognize even after a millennium and a half. But the effect for me was completely

undermined by a short appendix in which Ashe attempts to link Arthur/Riothamus

to the current heartthrob of the “Tiger Beat” set, Prince William, in a string

of once and future kings that smacks of the same romantic and political

motivation that influenced Geoffrey of Monmouth, Wace, Malory, Tennyson, and

all the other writers who had pandered to a particular monarch.

“Neither the medieval kings nor the

Tudor kings claimed to be literally descended from Arthur,” Ashe begins.

“The royal inheritance from him was collective;

English monarchs were the successors to his kingdom. Yet those who promoted this view may have

missed the most glorious connection of all.

Here the usual course of events is reversed. We do not confront a legend which scholarship

refutes. We confront a possibility,

unknown to legend, which scholarship reveals—a speculation, but an alluring

one.”

What follows is Ashe’s speculative

lineage: If Arthur was Riothamus,

and if had a wife before Guinevere, and if they had children,

then it might have been Cerdic who, according to the Anglo-Saxon

Chronicle arrived from the Continent in 495. The unknown wife, the fact that the Anglo

Saxon Chronicle gives Cerdic a different father, and many other details are

rationalized and explained in ways that would have made Geoffrey of Monmouth

proud. It is as if Ashe’s real motive is

to provide the link between Arthur and the Windsors that the Plantagenets and

Tudors sought; when the royal family becomes as dysfunctional as the rest of

us, elevate them through their Arthurian connections. (Ashe’s rationalization reminded me of an

article I read in a supermarket tabloid after Richard Burton died. It claimed that “Liz Can Still Have Burton’s

Baby!” even though he was dead and she was past menopause.—If an egg could be

harvested from Elizabeth Taylor and fertilized with a sperm bank donation that

Burton might possibly have left behind, then a surrogate mother just might be

able to bring the baby to term.)

To top it off, Ashe gives credit to

Arthur’s grave at Glastonbury even though Riothamus died on the continent. What makes an otherwise good historian behave

in such a goofy manner is at the heart of the medieval pilgrimage

experience. It is not just a willingness

but a wish to belive. Whether it was a

piece of the true cross or a piece of English oak didn’t matter if you believed

it was a piece of the true cross. New

Age pilgrims believe with Ashe that it is Arthur’s grave, and they are only the

most recent link in a long chain. The

original grave site was explored by archaeologists in 1963 and it was found

that there had been an ancient graveyard and that it had been

excavated in medieval times, leaving just enough proof for believers, while

allowing sceptics to continue as before.

One aspect of this whole Arthur’s grave

thing continues to bother me, and that is the question of why the tomb was so

ruthlessly and completely destroyed at the time of the dissolution of the

Abbey. Henry VIII, like his father and

all those numerous predecessors going back to the Norman Invasion, had

attempted to link himself to Arthur, and the fact that his hero’s supposed

grave was completely desecrated by his own men would seem to indicate that

Henry did not have much faith in the authenticity of the remains. That he passed up the opportunity to take

advantage of the public relations potential of moving the bones to another

site, makes me wonder if anyone in the sixteenth century had much confidence in

the Arthurian relics. Later in my

journey I would find persistent stories of the removal of bones from shrines in

anticipation of the arrival of Henry’s men: the remains of Edward the Martyr at

Shaftesbury, those of King Stephen at Faversham, and of course Becket’s bones

at Canterbury (which are still the source of speculation). In each case, local people are said to have

rescued the relics, but there is no such story at Glastonbury. Neither Henry nor the locals valued the bones

enough to preserve them.

Leaving Arthur’s grave behind, I began

my quest for the Holy Grail. I had read

that it was in a well and in fact there was a well in the remains of the Lady

Chapel on the Abbey grounds that was associated with Joseph of Arimathea which

for a time I mistakenly believed was the well. Another look at the local map informed me

that the Chalice Well was actually up the road a bit, on the way to Glastonbury

Tor.

The Abbey site has been re-consecrated

by the Church of England and continues to be a pilgrimage site. In late June a multi-denominational

pilgrimage attracts thousands of Anglicans, Catholics and even Orthodox

Christians. But the Arthurian connection

gives it a New Age spin and the other sites in Glastonbury go even farther

toward taking the town into a cosmic realm.

Glastonbury Tor is said to both an ancient Christian and a pre-historic

Celtic site, and at the Chalice Well things have slipped right over the

edge. Here the interplanetary vortex

reaches the earth in a big way.

At the well itself I found four women

standing completely still, eyes closed breathing in the essence. They had that wan skinny vegetarian

look. As the water flows downhill there

is a lion’s head fountain where you can drink the water and where a very

strange cast of characters was assembled.

All through the grounds people lay on their backs, barefoot, eyes

closed. At the fountain people were

touching, leading each other to the water, pouring it over their heads. The mystical quality for the faithful led to

shaking, moaning,and swaying. Several

people wore a silly smile on their face, one woman blew me a kiss. It all reminded me of that “Star Trek”

episode when the Enterprise crew goes to this planet where everybody is

loving and beautiful, but there is an undercurrent of weirdness. Not willing, however, to look a gift miracle

in the face, I went forward and took a sip of the water in my cupped hand (I

was not going to use the glass shared by all these people!) and then poured

some on my sore feet and knees. Tomorrow

will tell. I took a small piece of one

of the old yew trees as a relic.

There were lots of opportunities in the

nearby shops to buy crystals, magic potions, Celtic jewelry, prints of

pre-Raphaelite paintings of Arthur’s women, etc. I picked up a leaflet from a group looking

for financial support to build a sanctuary “dedicated to the sacred in all

spiritual paths.” It was to be “a new

idea for a new millennium” and would be located in Glastonbury because of the

“spiritual energies of this holy place.”

“Glastonbury

is the outer expression of the Isle of Avalon or Place of Apples, also known as

the Western Isle of the Dead. It is the

mythic home of the Nine Morgens, the Merlins, Modron, Brigit the Swan Maiden,

Mikael the Sun Lord and Gwyn ap Nudd.

Here the famed King Arthur lies sleeping with his Queen Guinevere until

the day of their return.

Glastonbury

also lays claim to being an ancient and present day Goddess site, an early

Druidical centre... In the present Glastonbury is described as the heart chakra

of Planet Earth and as a World Sacred Site it is a place of global spiritual

significance. ... Many people are drawn to Glastonbury by the atmosphere of

mystery.”

And some are driven away. It all just felt creepy to me and I reached

something of a low point upon reading this thing. Had this been what the Christian pilgrimage

meant to the pilgrims of medieval days?

As I was not looking for a meaningful encounter with Jesus and the

saints, so much as to understand the experience of perceiving the awesome power

that was transmitted to believers through their relics, I hoped to be able to

view this dispassionately, but I found that I have little patience with New Age

Pilgrims.

They do not believe less than the

average medieval pilgrim, if anything, they seem to enter more fervently into

the experience, and that is what I found so disquieting. People living in England in Chaucer’s time

had lived through the ravages of the Black Plague and had seen the government

shaken by the grasping for power that would lead to the War of the Roses. The Catholic church, which might have

imparted some structure beyond the vagaries of patriotism or nationalism, was

split under two different Popes for half of Chaucer’s lifetime. There was little “science” to speak of, the

vast majority of the people were illiterate anyway, and their lives were

controlled by an aristocracy that, if anything like the idiotic aristocrats one

reads about in today’s tabloids, must have made life a living hell. It’s no wonder they sought escape in a

pilgrimage.

But what is the rationale of these

people here in Glastonbury today? The

fundamental difference between past and present pilgrims as I see it is that

the medieval religious pilgrimage was a mainstream manifestation, and never

more than a temporary escape from the hardships of life. The literature of the New Age pilgrims

implies a rejection of the real world in favor of fantasy. The majority of mystic seekers at the well

appeared to be solidly middle class. It

was not poverty that drove them here, or plague, or oppressive regime, so what

was it? What misfortunes of love, or

failure at school, or loss of health, or dysfunctional family, or job crisis

led them to seek out the swan maidens and goddess sites and heart chakras and

mythic nobles? It can’t be an escape

from technology, because you can visit their web sites, and computer games that

take place in medieval landscapes on distant planets are readily purchased in

Glastonbury.

Occasionally I ask myself if historians

are not really in the business of creating a fantasy world of the past, and my

conclusion, in all honesty, is that they are not. Or at least that that is not my reason

for choosing history as a career. I may

occasionally live in other fantasy worlds, but not day in and day out as part

of my job. I tell my students (and I

believe) that history provides us with a way of looking at human beings and how

they respond to adversity, diversity, and how they live in and use the natural

world. While the people and events of

the past are intrinsically interesting, they are also worth studying for what

they tell us about the present. It is

only because we are constantly reinterpreting the past according to those

tenets important in our own society that historians stay in business generation

after generation. We ask different

questions of the historical evidence and we get different answers. And religious folk from the Wife of Bath’s

day to the present have always embraced a certain element of fantasy as part of

their faith.

The evening I spent at Wells Cathedral

I transcribed the words to the Blake poem that became the standard Anglican

hymn “Jerusalem,” and I thought about it several times that day. It begins with a reference to Joseph of

Arimathea bringing the young Jesus to England (on a prior trip to that on which

he brought the Holy Grail).

And did those feet in ancient times

Walk

upon England’s mountain green?

And was the holy Lamb of God

On

England’s pleasant pastures seen?

The setting of the tune is powerful,

but the message struck me as such a wonderfully queaky British fantasy. I mean, by God, this Jesus chap would hardly

go to all that trouble to be born of a virgin and made flesh and if he were not

going to come to England! Because I was

raised in an Irish-Catholic family in Spokane, Washington, I never even heard

this song until it became the hymn-of-choice of “Monty Python’s Flying

Circus.” Marching across the English

countryside I decided to make it my personal anthem.

Though Chaucer doesn’t mention it, the

Wife of Bath would probably have made one or more pilgrimages to

Glastonbury. It was an easy trip from

her home near Bath, and, after Canterbury, the most important pilgrimage site

in England. Here she would have seen the

grave of Arthur, not as the apologetic sign-on-a-stick that you see today, but

as a large and inspiring black marble tomb set directly before the high

altar. Her own decision to tell a tale

of a knight from King Arthur’s Court might have been influenced by such a visit

in earlier years when she was only a novice pilgrim.

Bring me my bow of burning gold!

Bring

me my arrows of desire!

Bring my spear! O clouds unfold!

Bring

me my chariot of fire!

I will not cease from mental fight,

Nor

shall my sword sleep in my hand,

Till we have built Jerusalem

In

England's green and pleasant land.

No comments:

Post a Comment